PATH

2008

Chipboard, surround sound system.

Sound:

Úlfur Hansson

Photos: diephotodesigner.de

The work has been presented in several exhibition venues, including Marible Lopez Gallery (2008), The National Gallery of Iceland (2009) and The Wood Street Galleries in Pittsburgh (2009).

PATH is part of the collection of the National Gallery of Iceland.

2008

Chipboard, surround sound system.

Sound:

Úlfur Hansson

Photos: diephotodesigner.de

The work has been presented in several exhibition venues, including Marible Lopez Gallery (2008), The National Gallery of Iceland (2009) and The Wood Street Galleries in Pittsburgh (2009).

PATH is part of the collection of the National Gallery of Iceland.

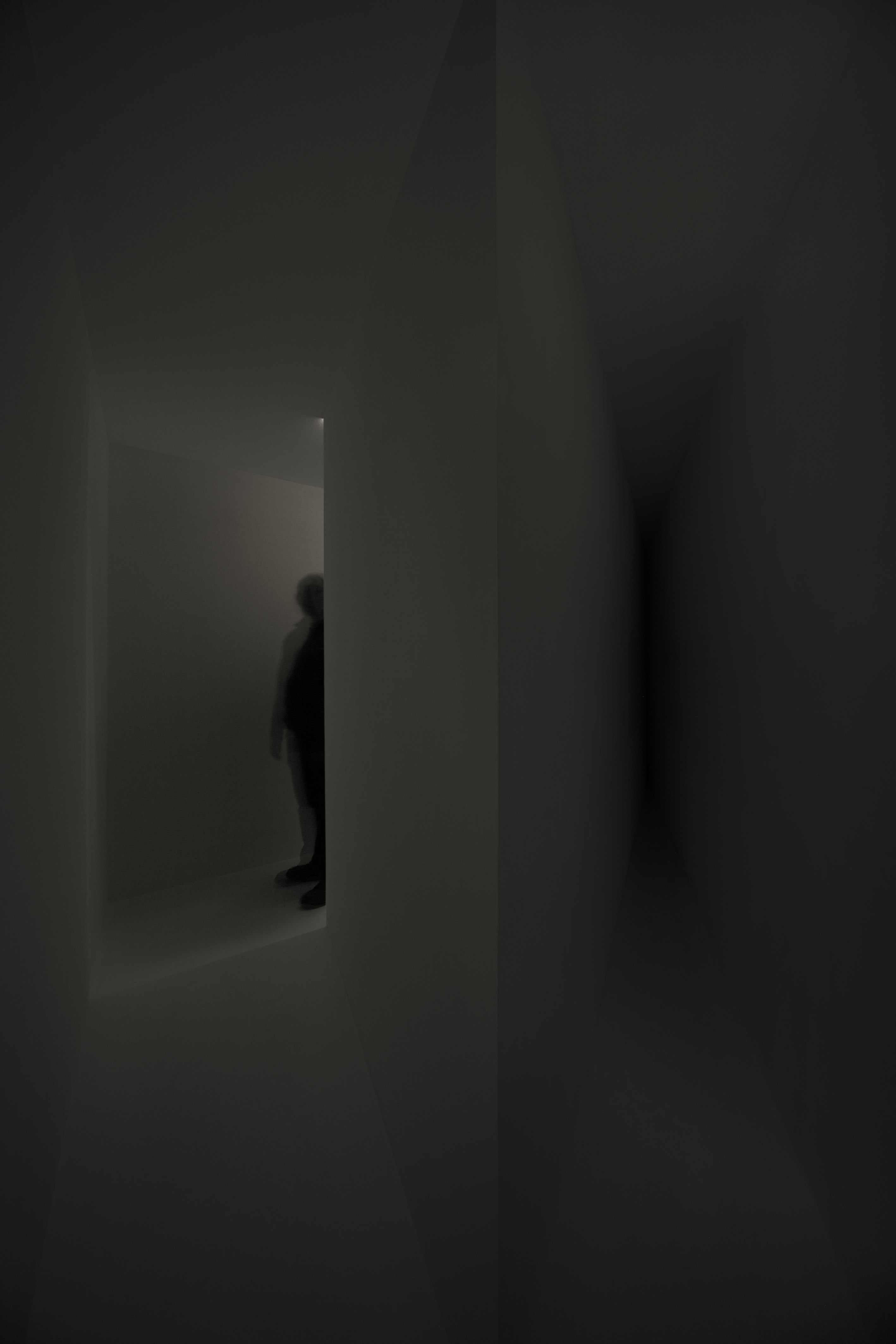

Path is a site-specific, labyrinthine installation that adapts uniquely to each location it inhabits. For its first iteration, the artist completely sealed off the commercial gallery space, rendering it inaccessible from the outside. Visitors were required to ring a bell at the entrance; in response, the door would open automatically, allowing them to enter one by one. This controlled mode of access heightened the sense of anticipation and disorientation from the onset.

The installation unfolds as a winding tunnel, its form dictated by the architectural constraints of the surrounding space. Designed to occupy as much of the site as possible, the structure is mapped directly onto the floor, resulting in a new, irregular shape with each version.

The only illumination comes from carefully postitioned vertical and horizontal slits within the walls, through which the bright light of the surrounding gallery filters in. This external light is fragmented by the structure´s sharp angles, manipulating perception - shadows appear as solid barriers, walls dissolve into voids, and light itself takes on the weight of architecture.

The installation unfolds as a winding tunnel, its form dictated by the architectural constraints of the surrounding space. Designed to occupy as much of the site as possible, the structure is mapped directly onto the floor, resulting in a new, irregular shape with each version.

The only illumination comes from carefully postitioned vertical and horizontal slits within the walls, through which the bright light of the surrounding gallery filters in. This external light is fragmented by the structure´s sharp angles, manipulating perception - shadows appear as solid barriers, walls dissolve into voids, and light itself takes on the weight of architecture.

BOOK

PATH - JOURNEY TO THE CENTER

by Elín Hansdóttir &

Rebecca Solnit

2012

Edited by:

Leah Whitman-Salkin

published by:

Crymogea Iceland

PATH - JOURNEY TO THE CENTER

by Elín Hansdóttir &

Rebecca Solnit

2012

Edited by:

Leah Whitman-Salkin

published by:

Crymogea Iceland

“The piece stripped you of uncertainties, of confidence, disoriented your sights unreliable, put you in a cloud of unknowing and set you on a path whose twists and turns and distance were unknown. This is perhaps close to our real condition in many ways that the assuredness with which we meet the world even when it turns out we don´t know what we´re doing or what to expect, even when the world surprises us and expectations don´t map possibilities. Which is to say it did what darkness and labyrinths do.”

Exhibition text by:

Ellen Blumenstein

Ellen Blumenstein

I IS ELSEWHERE

In her book, Installation Art (2005), the English art historian, Claire Bishop, describes different

categories of installations in terms of the role played in them by the viewing subject. This option

is both simple and evident, since a fundamental aspect of that discipline involves the spectator

having to venture into a spatial structure, thus becoming a constituent part of the work.

However, Bishop is still unique in not starting with the work (and only integrating the spectator at

a later stage), as she places the subject in the very centre of her analysis right from the outset.

This slant is particularly useful for an understanding of Elín Hansdóttir’s works. This young

Icelandic artist’s installations are grounded in the preconceived ideas held by the people that will

enter these spaces. By contending she can only conceive of her artistic production as a

process and that she does not work towards a finished object, Hansdóttir proffers an interpretive

framework which is implicitly valid for the would-be spectator, too. By thus departing from the

modernist advocacy for ‘instant capture’—along the lines of Clement Greenberg, for example—

Hansdóttir sets the time one spends in the installation at the very heart of one’s aesthetic

experience of the work.

This procedure may be construed in the tradition of James Turrell—Hansdóttir proposes spaces

which she fashions painstakingly and in great detail where minimal shifts in perception are

generated, based necessarily on the passing of time. While spectators may initially appear to be

an active element—they have to enter the installation, cross it and decide where to head, how

long to stay and when to get out—her works are actually geared to the passive spectator. The

latter does not create the experience but becomes its subject. Perceptive awareness of our own

body is not heightened; on the contrary, it is dulled. Consequently, the experience shakes our

faith in the stability of the world around us, and the control we exert over it, bringing home an

awareness of our own ‘decentralisation’ and ‘fragmentation’ (Bishop).

In a 2007 work, Hansdóttir clad a whole staircase in white-painted planks at the ZKM,

Karlsruhe, shifting the vertical plane and imperceptibly constricting the walls upwards, until they

practically caved in at the top, thereby depriving visitors of perceiving space naturally and

leading them to an awareness of how crucial space is in viewing themselves and their body.

For her exhibition at the Maribel López Gallery, the artist has designed a tunnel that tilts

downwards and zigzags across the gallery space. It has sharp edges, and light filters in at

irregular intervals through cracks in the tunnel walls, which have not been properly sealed. The

direction inside it changes so markedly that spectators soon lose any notion of where they are,

and where the exit lies.

In this work, Hansdóttir sets out to heighten awareness of our body through the loss of our usual

spatial bearings. Visitors are thus persistently exposed to a spatial experience of

decentralisation, disorientation, fragmentation and insecurity. Since there is no noticeable

physical difference between ourselves and the objects without, our ability to conceptualize our

surrounding space becomes jaded.

In this instance our customary points of reference, those we base our security on, become

disconcerting—we are unable to focus on the sharp edges and extremely acute angles that

mark changes of direction. Like some optical illusion, by attempting to touch and cling to them,

we end up confusing the commonplace with the real.

In her book, Installation Art (2005), the English art historian, Claire Bishop, describes different

categories of installations in terms of the role played in them by the viewing subject. This option

is both simple and evident, since a fundamental aspect of that discipline involves the spectator

having to venture into a spatial structure, thus becoming a constituent part of the work.

However, Bishop is still unique in not starting with the work (and only integrating the spectator at

a later stage), as she places the subject in the very centre of her analysis right from the outset.

This slant is particularly useful for an understanding of Elín Hansdóttir’s works. This young

Icelandic artist’s installations are grounded in the preconceived ideas held by the people that will

enter these spaces. By contending she can only conceive of her artistic production as a

process and that she does not work towards a finished object, Hansdóttir proffers an interpretive

framework which is implicitly valid for the would-be spectator, too. By thus departing from the

modernist advocacy for ‘instant capture’—along the lines of Clement Greenberg, for example—

Hansdóttir sets the time one spends in the installation at the very heart of one’s aesthetic

experience of the work.

This procedure may be construed in the tradition of James Turrell—Hansdóttir proposes spaces

which she fashions painstakingly and in great detail where minimal shifts in perception are

generated, based necessarily on the passing of time. While spectators may initially appear to be

an active element—they have to enter the installation, cross it and decide where to head, how

long to stay and when to get out—her works are actually geared to the passive spectator. The

latter does not create the experience but becomes its subject. Perceptive awareness of our own

body is not heightened; on the contrary, it is dulled. Consequently, the experience shakes our

faith in the stability of the world around us, and the control we exert over it, bringing home an

awareness of our own ‘decentralisation’ and ‘fragmentation’ (Bishop).

In a 2007 work, Hansdóttir clad a whole staircase in white-painted planks at the ZKM,

Karlsruhe, shifting the vertical plane and imperceptibly constricting the walls upwards, until they

practically caved in at the top, thereby depriving visitors of perceiving space naturally and

leading them to an awareness of how crucial space is in viewing themselves and their body.

For her exhibition at the Maribel López Gallery, the artist has designed a tunnel that tilts

downwards and zigzags across the gallery space. It has sharp edges, and light filters in at

irregular intervals through cracks in the tunnel walls, which have not been properly sealed. The

direction inside it changes so markedly that spectators soon lose any notion of where they are,

and where the exit lies.

In this work, Hansdóttir sets out to heighten awareness of our body through the loss of our usual

spatial bearings. Visitors are thus persistently exposed to a spatial experience of

decentralisation, disorientation, fragmentation and insecurity. Since there is no noticeable

physical difference between ourselves and the objects without, our ability to conceptualize our

surrounding space becomes jaded.

In this instance our customary points of reference, those we base our security on, become

disconcerting—we are unable to focus on the sharp edges and extremely acute angles that

mark changes of direction. Like some optical illusion, by attempting to touch and cling to them,

we end up confusing the commonplace with the real.